Excerpt from Examining the Evidence: Seven Strategies for Teaching with Primary Sources

From Strategy 3: Look for Bias

Manipulation of the Source

Bias can manifest itself in the editing of a source as well as the creation of it. A

potent example to bring up with older students is the diary of Anne Frank. Anne

Frank wrote her diary but she wasn’t alive to choose whether or what parts of the

diary should be published. Her father edited her diary and didn’t include many

entries where Anne wrote about sex or wrote less than kind or flattering descriptions

of the people in her life. For example, Otto Frank understandably did not

include an entry where Anne wrote, “Father’s fondness for talking about farting and

going to the lavatory is disgusting.” (A complete version of Anne Frank’s diary was

published in 1996 after her father’s death.) This example, instructive and memorable

as it is, may not be something you want to use with your students. For classroom

purposes, you could give your students this example. Anne wrote about their

helper Bep’s getting engaged. She says that the family isn’t happy about it because

they don’t think Bep loves her future husband. Otto Frank removed that entry

because Bep was still alive and he didn’t want to hurt her feelings.

Often, material will be edited for use in textbooks. Excerpts will be chosen for

their level of readability, for example, and difficult sections edited out. A photograph

can also be edited. Photographs are often cropped before they are published,

sometimes to fit space requirements and sometimes to make a better composition.

But it is also possible to crop something out of a photograph that someone does not

want us to see. A famous example of this is Stalin’s systematic removal of his political

enemies from official photographs. Visual examples of this can be found by

doing a simple Internet search. For example, a University of Minnesota web page

shows the removal of Trotsky from some Soviet photographs.

Let’s emphasize again that we are not saying that any of these sources are useless

as sources of information. But the fact that both images and text can be manipulated

points up the fact that it is dangerous to generalize from just one source.

Remember, “if your mother tells you she loves you, . . . ”

“The camera doesn’t lie” has lost a lot of currency since the advent of Photoshop,

but a photograph does not have to be significantly altered to show the bias of the

photographer. A few harsh shadows can make a kind, compassionate person look

like a villain. A few pretty props and a soft focus can make a selfish lout look like an

angel. Most photographic bias, of course, is much subtler than that, but having a

little bit of visual literacy can be very valuable in looking at a primary source photograph

as well as cartoons, drawings, and other forms of art that we intuitively feel

would be easier to “fudge.”

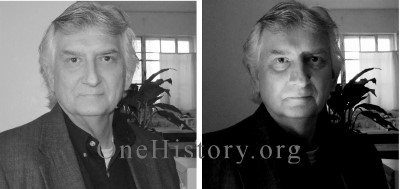

For example, it is possible to change the effect of a photograph simply by lighting

it differently.

Photographs of radio personality Mike Nowak. Photograph by Helen Tracy, 2013. Austin/Thompson Collection

When

asked to describe the character of the man on the left, viewers might use

words like kind and friendly. The print on the right would be much more likely to

elicit words like tense, annoyed, or even sinister.

|